1 Indian Institute of Management Sambalpur, Basantpur, Odisha, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

The poor and unorganized women artisans lack the physical collateral, and banks are wary to lend to them due to informational asymmetry regarding their creditworthiness. Social capital in a joint liability group enables the members to borrow from the banks. Due to the joint liability and dynamic incentive of higher credit limits, the members peer monitors each other to ensure access to finance. The research study aims to discuss the role of peer mechanisms in ensuring the success of lending to the poor and marginalized through self-help groups (SHGs) or joint liability groups. Since there is no study that discusses the impact of peer mechanisms on lending through SHGs, this study, for the first time, provides a conceptual framework for peer mechanism and their role in ensuring the sustainability of joint liability groups. This study uses the social constructivist paradigm and the grounded theory method to explain how the peer mechanism that comprises peer selection, peer monitoring and peer enforcement helps to improve the repayment rates under the SHGs linkage program. The data for the study are collected using 25 semi-structured interviews with the members of the SHGs and the heads of the self-help-promoting institutions. The analysis of data highlights that in a group social exchange, social control, social cohesion, sustainability, and social welfare, which emerged as categories after the open coding, are the main sources of peer mechanism. Further focused coding highlighted that mainly network relations, trust, and norms enable sustainability in the SHGs.

Microfinance, self-help groups, peer mechanism

Introduction

Muhammed Yunus, the person who revolutionized microfinance with the Grameen Bank model, once said, “I founded Grameen Bank to provide loans to those considered traditionally unbankable. Grameen Bank works with the poorest and often illiterate, providing uncollateralized micro-loans for tiny business enterprises by which they can lift themselves and their families out of poverty.”

A total of 1.7 billion people lack collateral and are financially excluded globally (Demirguc-Kunt et al., 2017; Ray, 1997). Due to information asymmetry, institutional financial institutions are hesitant to lend to the marginalized poor since it leads to high monitoring and screening expenses and deteriorating asset quality. Thus, credit market failure leads to the financial exclusion of the poor and promotes moneylenders (Stiglitz, 1990). Formal institutions do not lend to the poor; therefore, only low-quality lenders survive in the market (Akerlof, 1970; Ledgerwood, 1997; Weber & Ahmad, 2014). Microfinancing will affect society and the environment (Brundtland, 1987). Self-help groups (SHGs) lend to micro borrowers without collateral or creditworthiness by replacing social collateral with physical collateral and lowering transaction costs. Group lending and peer monitoring ensure financial inclusion of the unbanked people through access to local information. Information asymmetry can cause adverse selection—choosing the wrong person for credit distribution—according to a study (Jensen & Meckling, 1976).

Due to the joint liability, knowing that if a single member defaults, all the other members will have to pay on his behalf, the members monitor each other. Peer mechanism refers to the phenomenon through which members with limited liability select each other on the basis of association and knowledge using criteria such as profession, monitor each other, and enforce norms to ensure financial discipline in a joint liability group (Conning, 2005; Harriss & Renzio, 1997; Stiglitz, 1990). Groups help in mitigating the problem of adverse selection by member peer selection. Social contracts make members group agents and jointly liable. Group members share joint and limited liability. This social contract uses peer pressure and sanctions to increase debt collection, savings, and cost reduction (Angelucci et al., 2015; Basu & Srivastava, 2005). Social collateral substitutes physical collateral for financial inclusion (Pitt & Khandekar, 1998). Previous research shows what financial outcomes a group mechanism promotes: saving (Gugerty, 2007), higher credit (Deininger & Liu, 2009), income, asset ownership, recovery performance, and lower transaction costs (Puhazhendi & Badatya, 2002). Given the lack of physical collateral and knowledge asymmetry among needy Joint Liability Group members, there is no study on how the group mechanism promotes financial discipline and sustainability (Bastelaer, 1999; BIRD, 2019).

Literature Review

The agency theory, proposed by Jensen and Meckling (1976), investigates the relationship between borrowers and lenders within formal financial institutions. When applied to SHGs, the theory views the lender as the principal and the borrower as the agent. It emphasizes the information advantage that agents, or borrowers, may have over principals, such as banks, regarding creditworthiness and economic activities within the group. Agents can potentially exploit this information asymmetry for their own benefit, leading to issues like moral hazard in loan repayment and project riskiness. Microfinance, as argued by Baruah (2012), has the potential to drive social change and alleviate poverty. However, mission drift has made the subsidized banking model unsustainable for large commercial banks due to a lack of information on clients’ creditworthiness (Bhaduri, 2006). Pischke (1996) stresses the importance of financial literacy training for impoverished rural populations. Social capital and peer pressure, as highlighted by Sanae (2003) and Quidt et al. (2016), play a crucial role in ensuring the sustainability of group lending models like SHGs (Armendariz & Morduch, 2007). Joint liability groups, like SHGs, act as social contracts between marginalized borrowers and unknowledgeable lenders. In case of default, due to the joint liability, the entire group may face consequences, fostering a peer monitoring mechanism for better repayment rates (Stiglitz, 1990). Peer selection, monitoring, and enforcement have evolved as key aspects within group lending models, as discussed by Banerjee et al. (1994) and Besley and Coate (1995). Issues of adverse selection are addressed through risk matching and collective oversight. The presence of risky borrowers can lead to banks focusing on profits rather than social impact, a concept known as mission drift. Guttman (2008) challenges assumptions about borrower assortative matching, suggesting that dynamic incentives may alter behaviors within group lending models. Despite the evolution of these concepts, there remains a gap in understanding how joint liability groups facilitate financial inclusion for marginalized groups through peer monitoring. This study aims to develop a grounded theory of peer mechanisms within SHGs in India, exploring how peer monitoring functions in the context of the linkage program by integrating the principles of agency theory.

Problem Statement

Good…members seem to be getting new loans even if someone with the same group defaults. Why, then, do they bother to exert Peer pressure on defaulters? That is because otherwise, there would be a huge problem for all members at the center.

Existing studies highlight what the financial outcomes of a group mechanism are in promoting saving (Gugerty, 2007), increased credit (Deininger & Liu, 2009), income, and asset ownership, recovery performance, and reduced transaction costs (Puhazhendi & Badatya, 2002). But there is a shortage of research on how the group mechanism promotes financial discipline and sustainability in the context of the SHG linkage program. This study will most likely be the first to examine how asymmetric information and agency affect joint liability group efficiency and effectiveness.

RQ1. The broad research question is, how does the peer mechanism work in the context of the SHG bank linkage program?

Research Methodology

This section describes how the data were collected and analyzed and how codes, concepts, and patterns evolved. It depicts the conceptual development process related to a theory’s development.

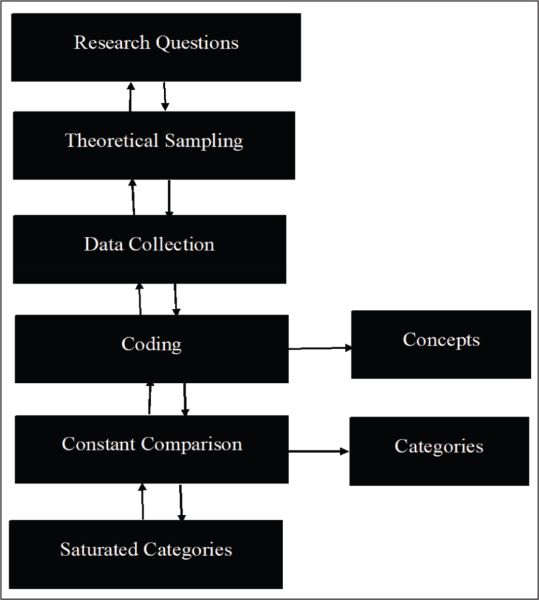

The first step in grounded theory is the development of the research questions, as shown in Figure 1. The data collection and analysis to develop grounded theory are repeated iteratively. This is done to make the development of patterns, themes, and multidimensional correlations easier so that the collected data may be compared, categorized, abstracted, and conceptualized more easily. Theoretical sampling and coding are used to collect and analyze data until theoretical saturation is reached and a dense theory emerges. The abductive theory-building method was used to understand the phenomenon of peer monitoring in a group lending scenario. The data were collected and analyzed simultaneously to understand the group’s real-life problems. The abduction illustrates the process of making creative inferences and verifying them with more information to ensure the authenticity of data. It helps to mitigate Hume’s problem of induction and Kant’s problem of naïve empiricism. This study is based on the grounded theory method (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). The data coding stages in this study are open—focused on the development of categories as suggested by Charmaz (2006). In this method, the problem is allowed to emerge from the data. The semi-structured interviews were conducted to generate the data. Data from the interviews and observations are used to discover emerging concepts and relationships.

Figure 1. Research Methodology.

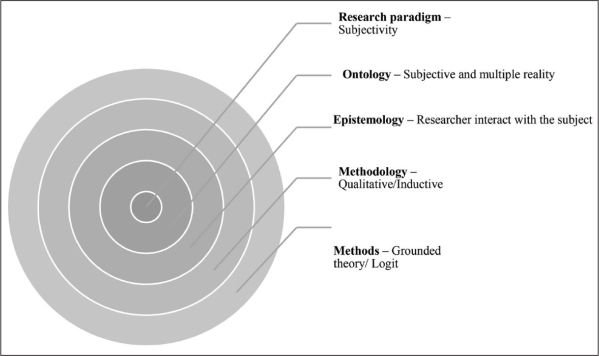

Philosophical Stance for the Research Study

Because this study is exploratory, the various research strategies recommended by Saunders have been used to conduct grounded theory research. The researcher’s philosophical stance or worldview assumptions regarding the nature of reality impact the methodology adopted for research and the interpretation of results (Creswell, 2012). This comprises a set of beliefs that guide action, which have been referred to as research paradigms (Lincoln, & Guba, 2000). The research paradigm is referred to as ontologies and epistemologies (Crotty, 1998). Despite using the Glaserian and Charmaz data coding method, the study builds theoretical sensitivity by referring to literature in the second stage. The emerging codes were continuously analyzed to determine how they fit the theory. Social constructivism as an epistemology is an interpretive approach focusing on how people make sense of the world, primarily through sharing their experiences with others (Easterby-Smith et al., 2002; Saunders et al., 2009); the sample size is determined initially through purposive sampling. And as the codes emerged, sampling was done using theoretical sampling. The codes were generated based on the constant comparison till theoretical saturation was achieved. It was done to take care of the theoretical sensitivity.

Data Collection

In this study, broad, open-ended questions, narrative semi-structured interviews, and the historical document appraisal approach have been used to collect the data and understand the events. A constructivist approach was adopted to collect data. For example, the first question is, tell something about the group formation. While conducting the exploratory interviews, due consideration was given to the principled sensitivity to the rights of others. Before collecting the data, the access was negotiated, and consent taken was informed consent to avoid deception and provide protection to the privacy of the members. Memoing was done simultaneously with data collection through observation. Despite assertions by Saunders et al. (2009) that interviews can be structured or semi-structured, in this study, the semi-structured interview and open-ended interview approach have been adopted. In addition to interviews, archival records, internal reports, and news articles were used to obtain data. The publicly available data includes the secondary reports such as the handbook on SHG linkage (DAY NRLM, 2017; World Bank, 2020) and videos, documentaries and clippings created by various agencies such as world bank, commercial bank (DAY NRLM, 2014) and other references available online and mentioned in the study. In this study for data triangulation, the SHG bank linkage handbook was referred to identify the process of financial inclusion. This process was further authenticated through the semi-structured interview with the villagers and micro-borrowers. Data triangulation involves collecting the data from multiple sources, such as interviews and secondary reports and publications, to increase the credibility and validity of findings (Campbell & Fiske, 1959). After data collection, negative case analysis and member checks were performed to increase the validity and reliability of data.

Data Analysis

The constructivist grounded theory drives the study (Charmaz, 2006). The problem is explored using the constructivist grounded theory three-stage method comprising of open coding, focused coding, and theoretical coding. As a result of the grounded theory methodology, the purpose of this study was to collect information on how the peer mechanism functions within the context of self-help group bank linkage programs in India to assure the achievement of the group’s revenue enhancement and social welfare objectives.

Within-case Analysis

Interviews and publicly available data are used for analysis (Eisenhardt, 1989). The codes are derived from the data using intensive abductive grounded theory coding. The interviews were transcribed, triangulated, and then supplemented with secondary data. Coding revealed various themes and constructs. The primary focus was on how the groups obtained formal credit without physical collateral or creditworthiness (Eisenhardt, 1989). Within the case, analysis familiarized researchers with data and paved the way for cross-case research.

Cross-case Analysis

The cross-case analysis was performed after the first two rounds of data collection. This ensures case replication reliability (Eisenhardt, 1989). A cross-case analysis is done using pairwise case comparisons. The stakeholders and groups were selected based on the within-case analysis. The SHGs are compared and contrasted based on linkages, that is, (a) those that have taken loans through the SHG bank and those that rely solely on internal loans or loans from other formal or informal sources, (b) groups formed and mediated by SHPIs or NGOs, and (c) clustered groups. This method helped to identify patterns across SHGs funded by formal sources like banks and internal sources like savings. The findings suggest that more successful women entrepreneurs who form collectives use group mechanisms more extensively than those who do not.

Coding

Coding is an interactive process (Charmaz, 2006). In this study, coding has been used to delimit the research, as suggested by Charmaz (2006). This study collected and analyzed data simultaneously. Despite the literature review, a mix of inductive and deductive coding or abduction has been used to develop the codes. These codes go through a second coding cycle for higher categories or themes. After generating the significant categories, the existing literature is used to create the theory. The data were arranged before analyzing it. Memos are prepared for each interview and interaction to summarize the main points. The data’s theoretical sensitivity was considered when interviewing SHG members; the researcher can use existing theoretical knowledge to interpret the observed phenomenon. Theoretical sensitivity is the ability to see with analytical depth. This study is based on memoing, line-to-line data analysis, and recording thoughts and feelings during the data collection. Further, the existing literature has been used to build theoretical sensitivity, but with caution. During the preliminary studies, some 200 codes were generated that were filtered into 60 focused codes. Six key themes ultimately emerged from the data.

Open Coding

The data for the study were collected using the exploratory interview approach. In the first phase, the data were analyzed using the open coding technique. Coding was done in two cycles. In the first cycle of open coding, codes were small words that captured the essence or attribute of verbal data. The second coding cycle through memoing provided a conceptual framework for the codes. The data are coded and analyzed sentence by sentence, asking the following questions:

(1) What is happening in the data, and what is this observation sentence a study of?

(2) What is the primary concern in the data?

(3) What is the category that is emerging from the data?

(4) What actions are people taking for granted in the data?

(5) What are the common problems that people face?

The emerging data were analyzed using gerund coding (focusing on human interactions) to generate the open codes; these open codes represent the incident, idea, or process and are the foundation of all theory building. The first step in the open coding was transcribing the interview and then using line-by-line coding. These initial open codes help the data to be transformed into categories. The open codes were prepared from the data summary of the data. From the first interview onwards, the process was repeated iteratively until theoretical saturation or sufficiency was achieved. The data was collected and analyzed simultaneously using the memos. The scholarly literature is not consulted in the initial stages. But the categories started emerging after the open coding of the first 10 to 15 interviews. Initial codes were created, and substantive codes were derived as categories. At this stage, the scholarly literature was consulted & coded to generate theoretical sensitivity. Theoretical sampling was used to generate the concepts, maximize the variations in the concepts, and densify the categories.

Focused Coding

Focused coding was done based on Meaning, Action, Challenge, and Results (MACR) approach. The constant comparison was done to analyze the hidden patterns in the data. To build the theoretical sensitivity in the data, focused coding was done in order to delimit the emerging patterns in the data

Codes to Categories

Identifying in vivo codes led to more descriptive codes and higher abstraction of analytical codes through open coding. These codes form the foundation for theory development. After the initial stages, we began collecting data to develop categories and properties using theoretical sampling. Theoretical literature was referred to at this stage multiple times to facilitate memoing and coding. The data were rigorously coded line by line to facilitate theoretical linkages.

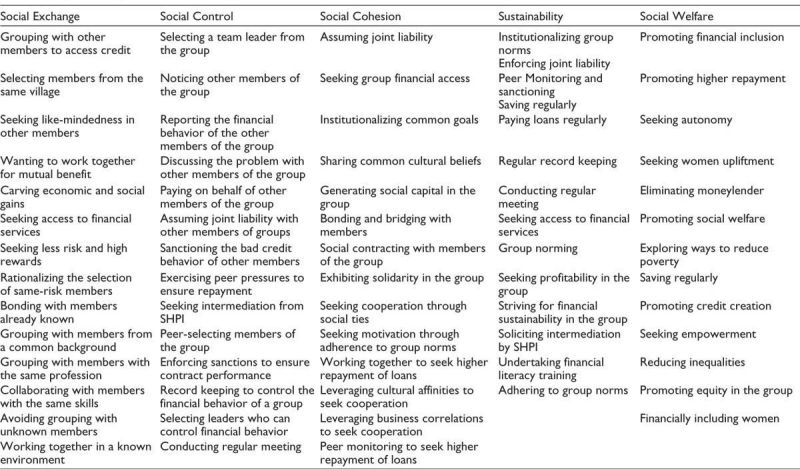

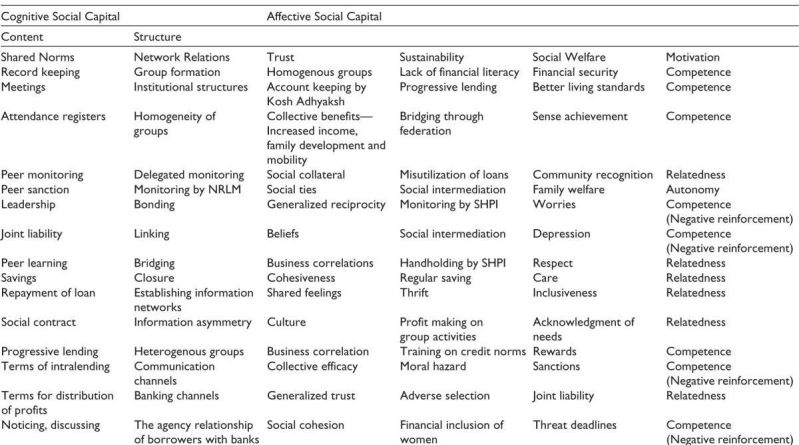

Patterns and Concept Governance

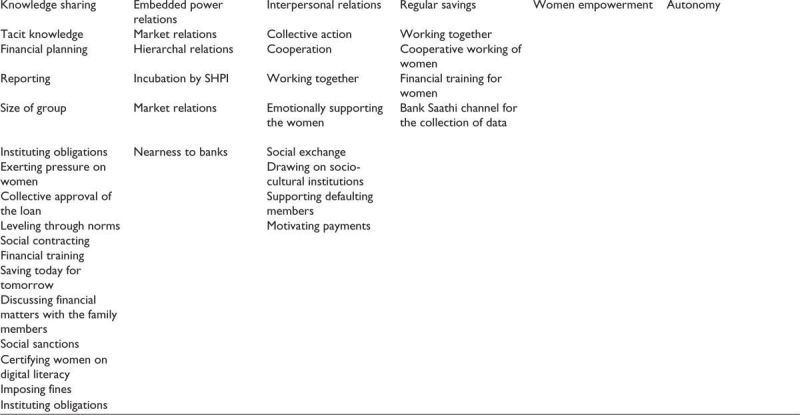

During data analysis, the concepts grew, and a series of open and tentative coding emerged. The categories are identified to provide conceptual information. Table 1 highlights the main categories that have emerged through various phases of data analysis.

Table 1. Open Coding.

Results

Narratives from the Ground Realities

Microfinance is much more than simply an income generation tool. Directly empowering poor people, particularly women, has become one of the key driving mechanisms toward meeting the Millennium Development Goals.....

Mark Malloch Brown, Chef de Cabinet,

Office of the Secretary-General to the United Nations

There are existing studies that address the question of why poor people are not able to access financial services. But there is a lack of studies on how social innovation, or the SHG, enables the members to access financial services.

Identification of Categories

The categories were identified using the questioning technique: who, where, when, how? The theory has two parts: categories and properties. A category is a theoretical element. The property is the dimension of the conceptual element of the theory. For example, five categories for microfinancing are social exchange, social control and contingency planning, social cohesion, sustainability, and social welfare. It also involved questions about spatial and temporal context. These categories are defined in the context of an agency relationship. The borrowers are the agents, and the lenders are the principal. The interview excerpts and verbatim highlight the process of identification of the categories. The details of the categories are given below:

Emerging Categories

We now have five categories:

(1) Social exchange

(2) Social control

(3) Social cohesion

(4) Sustainability

(5) Social welfare

Categories and Properties

(1) Social Exchange: Social exchange highlights how the group members leverage the group affinity and social capital to derive financial benefits in terms of access to loans greater than the individual capability to raise loans. The exchange of social capital for access to loans leads to the social contract to leverage internal savings and access external loans. Members endorse a social contract with joint liability that leads to generalized reciprocity. Besides that, strategic communication through the enforcement of group norms leads to the development of the targeted mission to achieve the group’s purpose of financial inclusion.

Every group has a particular purpose; they exist for a goal that must be communicated and fulfilled. Trust also leads to group identity, social capital, adherence to norms, and repayment of loans. Thus, the collaborative and collective power ensures access to credit and financial sustainability through regular repayments. Within this category, information asymmetry refers to the lack of information about the group members’ creditworthiness to formal financial institutions. It concludes that information sharing occurs in closed networks or bonding among members. This category highlights how the group generates and shares information about its members, facilitating finance access. This category explains how the banks, through groups, get the right to access information about the creditworthiness of the group members, who individually lack physical collateral. The social structure of groups facilitates institutional discourse that has its credibility.

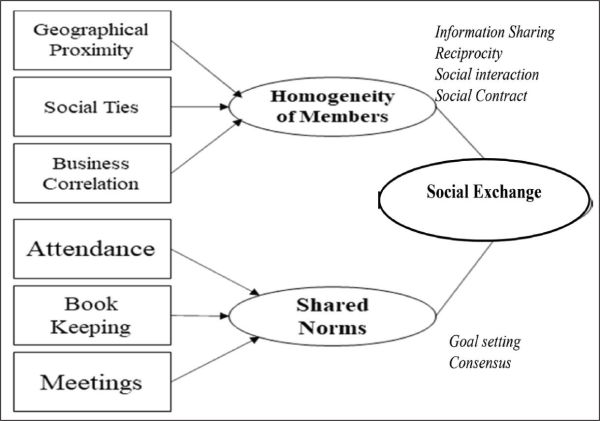

Figure 2. Research Design for the Study.

Figure 3. Category 1—Social Exchange.

The data analysis revealed that the group members engage in frequent social interactions. Groups are formed based on homogeneity, which means that members share a common ground that leads to collective power, group affinity, and trust, which leads to generalized relationships. They share a profession and ethnicity, making them a source of information. In a group, the exchange of information about financial goals through socialization depends on information flow capability. Information flow capability depends on community connectedness, homogeneity of groups, and relational networks. In a group, the information flow capability is very high. Sharing information and intermediation lead to consensus and reciprocity. This communication facilitates social contracts and social exchanges. Once in the social contract, the members develop an economic goal. Knowing that in case of a single member default, the bank will not extend the loan to the group, the members cooperate. This human behavior is rationalized due to the incentive compatibility constraint by banks in the form of progressive loans to groups that pay all their loans in time and penalize the defaulting group. The fundamental basis of social exchange is the commitment of the members to perform their group duties, repay loans, and exchange information. Communication impacts relational governance development depending on the network’s information flow capability and represents the category of social exchange.

(2) Social/Control:

It is the social process of group life that creates and upholds the rules, not the rules that create and uphold group life

This category shows how a group with homogeneous members uses peer influence and sanctions to monitor and control. In a group, members are bound by a social contract, and the social control is operationalized through reinforcement. The dynamic incentive of the progressive loan in case of loan repayment and sanction in case of default by even one group member works as a stimulus. This contract provides joint liability for the group and limited liability for the individual. In case of default by one member, all other members have to repay the loan. Influence and control are rooted in the cognitive and cultural norms of the social contract. Social Norms facilitate the enforcement of the social contract. The cultural component refers to social norms and sanctions. And the cognitive elements of the social contract, that is, refer to the group norms such as maintaining minutes of meetings and books of account. A transcribed interview from a master craftsman in a SHG is mentioned in Transcript 1.

|

Transcript for Interview 1 Interviewer: What occupations do the members of your group engage in? Respondent: The women in our group have traditionally been involved in crafting leather handicrafts, a vocation passed down through generations. Many artisans in local markets continue the legacy of producing these handicrafts. Interviewer: How do you address defaulting members within the group? Respondent: In cases where members are unable to repay their loans, all group members come together and visit the defaulter’s home as a collective effort to address the issue. |

Clearly in this interview, as per the respondent, the group has pursued the art of making the leather products, and as per the master artisan craftsmen, the artisans use peer pressure to ensure timely repayment of loans. The cognitive norms in a group become operational through the social contract and bank sanctions. Peer monitoring by the joint liability of the group and limited individual liability also leads to social control in a group. In a group, social norms facilitate the enforcement of the social contract. In a group, the community’s norms to save and repay loans facilitate control through reinforcement. Social contracts and joint liability play an essential role in social control.

|

Transcript for Interview 2 Interviewer: What is the primary occupation of the members in your group? Respondent: Our main vocation involves crafting pots from mud and firing them to create terracotta. Interviewer: In what ways does the group provide assistance to its members? Respondent: When a member faces challenges, such as being unable to craft a seat for a Ganesh Murti, the other members come together to offer support and help them overcome the obstacle. |

As per Transcript 2, the group members cited that the group is involved in making terracotta pottery. Regarding the group mechanism, the respondent highlighted that if a member is making a Ganesh Murti and they cannot make the seat for the lord, then the other members help them. Thus, the cooperation in the group improves the solidarity of the group.

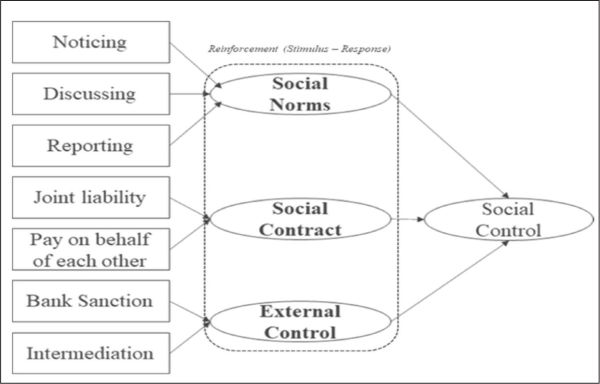

Figure 4 highlights the category of social control. The social norms in the form of noticing, discussing, reporting, social contracts, and bank sanctions lead to open code social control.

Figure 4. Category 2—Social Control.

(3) Social Cohesion: Solidarity in a group promotes cohesion and camaraderie. It helps them build relationships, trust, and cohesion, which drives financial sustainability. Geographic proximity, puritan values, and shared vocation unite a group and create a common bond in the form of social capital. Task dependencies and business correlation, and cultural affiliations lead to like-mindedness. Social ties, cultural affiliations, and task dependencies lead to cooperation. Cooperation and like-mindedness lead to solidarity. Solidarity leads to motivation for peer learning and adherence to norms. Adherence to group norms leads to higher loan repayments.

|

Transcript for Interview 3 Interviewer: What is the primary vocation of the group? Respondent: The self-help group consists of Dhokra artists residing on the outskirts of the village in Odisha. Interviewer: What do the members manufacture? Respondent: The artisans specialize in the Dhokra art, employing metal casting techniques to create a diverse range of artifacts, including divas, pots, and animal figurines. Interviewer: Do all the members engage in the same art form? Respondent: Yes, all members are dedicated to preserving this traditional art form that has been passed down through generations. Interviewer: How does the group support its members? Respondent: The shared professional homogeneity fosters a strong sense of camaraderie and connectedness among the group members |

As per Transcript 3, another example of solidarity and cohesion is the Dhokra Art group that resides in Orissa, India. Dhokra art is pre-Mohenjo-Daro and Harappan art from Bastar, Chhattisgarh, India, and depicts Eastern Indian heritage. In an SHG formed by Dhokra artists, the master craftsmen emphasized that the artisans reside at the outskirts of the city. According to the master craftsmen, the group has been preserving this ancestral art form for ages. These skilled artisans use metal casting to create a wide array of artifacts, including diyas, pots and animal figurines. The SHG leader cited professional homogeneity as a source of solidarity. This story shows how ethnicity and heritage unite a community. Repayment of loans is determined by trust. The member said the group may not eat but will repay the loan. Honesty promotes group cohesion.

|

Transcript for Interview 4 Interviewer: What is the composition of your group? Respondent: The group consists of 12 to 13 women and 7 to 8 men who specialize in crafting silver jewelry from their homes, offering expertise and training to new members. Interviewer: What is the source of funds for the group? Respondent: The source of funds includes shared savings and profits distributed among members based on goods sold. Interviewer: What is the control mechanism for the defaulting members? Respondent: In case a member is unable to repay a loan, the group collectively covers the repayment. Financial discipline is maintained through counselling of defaulters and accountability measures by designated leaders. The group focuses on creating unique Adivasi designs like khatwah, bhongiri, and phechwa, which are highly valued within the Sonar community. They are hopeful for opportunities through the new brand Ajiva. |

As per Transcripts 4 and 5, in an interview with the sculpture-making group, the master artisan highlighted the group’s focus on crafting the Green Ganeshji. According to the respondent, the group engages in creating Ganeshji sculptures from March to September. They collect mud during this period, which is sourced from the mountains and brought to the riverbank for their artistic endeavors. The artisan mentioned that the Pach art form holds a significant place as the ancestral tradition of the group. Furthermore, he mentioned that the unity of goals within the SHG serves as a catalyst for fostering unity among its members, drawing them together in a shared purpose and vision. This shows how cultural repertoire can encourage unity. Group solidarity is also attributed to government programs like Ajeevika or DAY National Rural Livelihoods Mission (NRLM). Norms promote unity. It shows how members of a SHG leverage existing social relationships (cognition and cultural affiliations) to create new network relations (bonding and bridging), leading to economic resources. Moreover, the shared norms regarding bookkeeping lead to higher repayment of loans in a group.

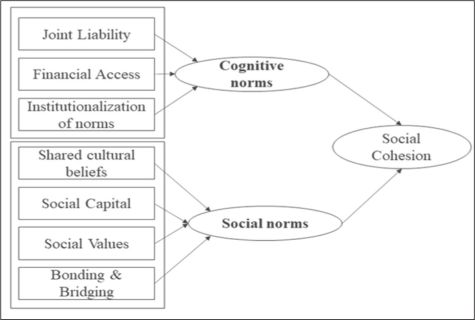

To sum up, two kinds of norms, that is, cognitive norms and social norms in a group, lead to solidarity. In a group, members institutionalize the common goal through a social contract. Members use shared bookkeeping norms to embed cognition. They also use shared cultural beliefs to build community. Group membership forms horizontal bonds. Common culture and heritage lead to group solidarity and cohesion. Lower borrowing costs and reliance on informal networks have increased group solidarity. According to a member of a silver jewelry SHG, SHG helps reduce reliance on informal moneylenders or Mahajan. Culture influences group solidarity. Table 1 represents the category of social cohesion.

|

Transcript for Interview 5 Interviewer: What is the vocation of the members of the group? Respondent: We make green Ganesh Ji. From March to September, we’ll make and sell mud-made Ganpati when mud comes from the mountains to the banks. Pach is our ancestral art form Interviewer: How does the group help you? Respondent: When community groups face the same financial goals and lender sanctions, it promotes unity |

In another interview, the respondent emphasized the role of SHGs in reducing reliance on informal moneylenders, known as Mahajans, and highlighted the impact of group culture on fostering solidarity. The member explained that within the group, if a member is unable to repay a loan on time, all members come together to support the defaulting member in repaying the loan. Furthermore, the respondent stressed the importance of trust in loan repayment, emphasizing that social ties and trust are built through work-related, bilateral, and task dependencies. The master craftsman pointed out that cohesion within the group is influenced by leadership, despite the fact that some members may be illiterate. In the group, leaders, known as Adhyaksh or Koshadhyaksh, are selected to assist members in preparing financial records, documenting meeting minutes, and conducting group meetings.

Thus, there are two sources of solidarity, that is, cognitive and affective embeddedness of norms. Figure 5 represents the category of social cohesion.

Figure 5. Category 3—Synergy Perspective to Integrate Networks for Generation of Social Cohesion in Groups.

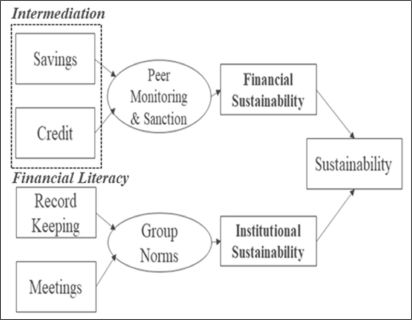

(4) Sustainability: The future productivity of existing systems is called sustainability. The central issue in finance is whether the existing financial processes and structures are sustainable. The process of sustainability was defined initially as structure process stability. This concept now includes financial and institutional sustainability. Sustainability is the system’s future production ability to repeat the performance. The financial viability of a SHG depends on access to savings, thrifts, loans, credit rotation, and loan repayment.

|

Transcript for Interview 6 Interviewer: How does the self-help group help you? Respondent: SHG helps reduce reliance on informal moneylenders or Mahajan. If a member can’t pay, we all do and the repayment of loans involves trust and mutual dependence. The trust in a group and social ties and trust result from work-related, bilateral, and task dependencies Interviewer: What is the importance of leadership in the group? Respondent: Leadership affects group cohesion. The group members are not that literate, and the group selects Adhyaksh and Kosha Adhyaksh for the group. These leaders guide the group members in preparing books of accounts, minutes of meetings, and conducting the meetings. This also promotes solidarity among members |

In one interview, a respondent emphasized that the sustainability of the group is ensured through literacy and capacity building. Thus, intermediation leads to adherence to group norms. And adherence to group norms leads to the institutional sustainability of groups. The respondent emphasized the group’s weekly meetings, highlighting the close monitoring and support system among members. The respondent mentioned that members utilize social media platforms such as WhatsApp to stay connected and reach out to each other. Additionally, the respondent highlighted the peer monitoring system within the group aims to promote sustainability by encouraging members to support and hold each other accountable. The respondent also mentioned that the group leader has the authority to remove a member from the group and can request the banking committee to investigate any defaults. According to the respondent, the peer mechanism plays a crucial role in promoting sustainability within the group, fostering a sense of responsibility and accountability among its members.

|

Transcript for Interview 7 Interviewer: How do the members in group collaborate? Respondent: We meet weekly and closely monitor the group. We use WhatsApp to reach our members Interviewer: What are the benefits of the group formation? Respondent: In a group, peer sanction and monitoring promote financial sustainability. The Adhyaksh is in charge of records, and a defaulter is expelled from the group. We ask the state banking committee and SHPI to investigate the defaulters. The members exercise peer sanctions to ensure the financial sustainability of groups |

As per the Transcript 7 in another interview, members emphasized that upon joining the group, leaders instruct them on the significance of maintaining proper financial records. Furthermore, the group leader mentioned that the involvement of the bank and the NRLM in monitoring the group’s finances plays a crucial role in ensuring effective financial management. In yet another interview, we discovered that the group’s sustainability is impacted by the financial literacy of the members.

|

Transcript 8 Interviewer: How does the group support its members? Respondent: Upon joining, we emphasize the significance of bookkeeping. Training provided by the self-help group, along with oversight from the bank and NRLM, plays a crucial role in effectively managing the group’s finances, contributing to its sustainability. |

Figure 6 highlights the category of sustainability. Intermediation leads to better savings and credit. Peer monitoring and sanctions improve the financial performance of the groups and lead to financial sustainability. Moreover, the financial literacy of members leads to better record-keeping and meetings. Through accepted group norms, the group can achieve institutional sustainability. Thus, financial and institutional sustainability leads to sustainability in the group.

Figure 6. Category 4—Sustainability.

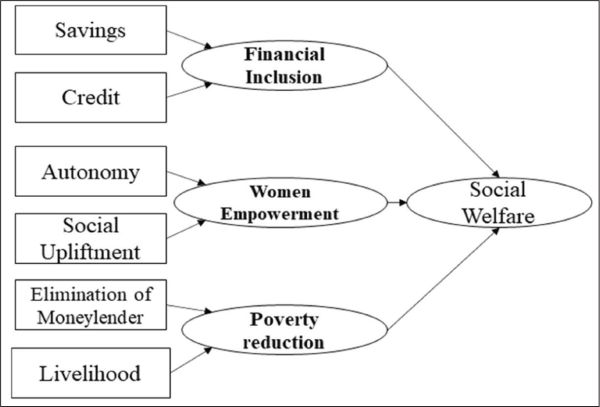

(5) Social Welfare: The study confirms that the SHG members benefit significantly from the SHGs. According to the procedural utility theory, these groups are instrumental in promoting the group’s welfare. These groups lead to the instant gratification of the individual’s needs. The members achieve positive well-being through microcredit, including positive affect (better financial well-being, financial achievement, better community standing, social welfare, and better family relations). Individuals’ welfare can be further classified as (a) cognitive evaluative, which refers to the benefits of community membership: better finances, community, and health. The groups also provide hedonic experiences. The hedonic experiences include (a) autonomy, (b) relatedness, (c) competence, and (d) self-actualization. The feeling of self-actualization and better life experiences due to better living standards and achievement in life, family, and community are included in the cognitive evaluation. Debt can cause (a) depression and (b) worry. The procedural utility is defined as (a) autonomy, (b) connectedness, (c) trust, and (d) competitiveness. Thus, joint liability groups through microcredit provide procedural utility, leading to women’s empowerment and self-determination. In one interview, the member said, the government is helping the women members gain confidence, self-efficacy, and trust.

In a group, regular savings and credit lead to financial inclusion, and social upliftment leads to women empowerment. Further, joint liability groups generate livelihood and eliminate the money lenders, reducing poverty. In an interview, the respondent highlighted. According to the respondent, the group members create small diyas, big diyas, and mud lamps, which are then baked in a terracotta fire. The respondent noted that this diversified product range has significantly enhanced the group’s effectiveness.

RQ2: What is the impact of peer mechanism on the financial sustainability of the SHGs?

And the focused codes for the study are mentioned in Table 2.

Table 2. Focused Codes.

Focused Coding

RQ1. How does peer mechanism work in the context of the SHG bank linkage program?

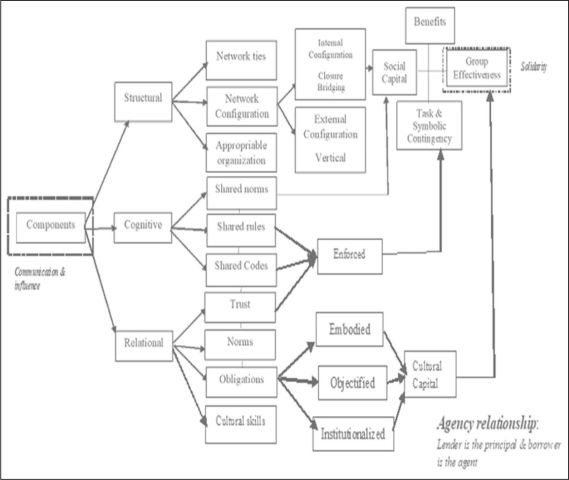

Focused coding was done based on MACR approach. The constant comparison was done to analyze the hidden patterns in the data. To build the theoretical sensitivity in the data, focused coding was done in order to delimit the emerging patterns in the data. The major objective at this stage was to verify how the categories relate to the concept. The core category of a unique social dynamics known as peer mechanism started emerging at this stage. At this stage, the categories were further refined to extract four concepts, namely, network relations, shared norms, trust, and motivation. The category of social exchange hinges on network relations and trust types. There are significant differences between the categories and subcategories. In a horizontal structure, the group members communicate informally and frequently and socialize. In a linking relationship with the bank, the members share information formally through the state-level banking committees, MIS dashboards, and bank Sakhis. In a federation, the groups interact through the leaders and meetings. Social control is informal and personal in the case of a group member and highly formal in linking relationships with banks. Group members exhibit the high level of solidarity in a bonding relationship that is not exhibited in relationships with clusters and federations. Influence and social control depend on norms and network relations. From the initial code analysis, three concepts—social exchange, social control, and social cohesion—lead to sustainability and social welfare, which is classified as social capital. What affects the group? Who, what, and how does the peer mechanism work? How does the social process work? From the data analysis, it is discovered that group works through the social capital and norms. Social capital is operationalized through enforcement, trust, and motivation, which leads to social welfare and sustainability. These concepts of social exchange, social control, and social cohesion institutionalize relationships and content into norms. Social capital is structural, relational, and cognitive. The structure includes network, ties, configurations, and appropriable organization. The cognitive dimension includes shared codes, rules, and narratives. These two dimensions of social capital interact, that is, structure and norms. Social capital varies depending on the external and internal network configuration. And relational components refer to trust norms and obligations. The phenomenon under investigation is peer mechanism and financial access through the peer mechanism. The members in an SHG communicate and influence each other. The members share their experiences and financial decisions and influence each other to exercise prudence in managing money and finances. The group members in a group communicate, influence, control, and collaborate. Structural social capital refers to the network relations, configurations, and organization forms. The network relation comprises of (a) closure, (b) bonding, and (c) linking. Closure refers to the relationships that originate from the social background. And the linking relationship refers to the relationship with the banks. These relationships are further classified as the internal and external configurations. Internal relations refer to the bonding, and bridging relationships are the relationships in the group context. Cognitive relationships refer to the enforceable and acceptable norms as part of the social contract. And the relational social capital refers to the expectations and the shared perceptions among the group members. The enforceable norms are communicated as the group norms. This refers to the cognitive component of the social capital, that is, codes, rules, and the norms. Then there are relational networks in the group due to the social ties among the members, business correlations among the members, and the cultural beliefs that are institutionalized in the groups. This is the cultural capital. Social capital, cultural capital, and cognitive norms lead to solidarity, reciprocity, and task contingency. The emerging pattern became more apparent during this stage, and the core category of peer mechanism started emerging.

Figure 7. Category 5—Social Welfare.

Figure 8. Focused Coding.

Discussion and Analysis

The Emergent Theory

The analysis of data and codes reveals that at the heart of microfinance is the issue of financial exclusion of the poor and marginalized, particularly women (DAY NRLM, 2017). The analysis of interviews highlighted that in the village community, the women and marginalized poor do not have access to the physical collateral, and banks are unwilling to lend them money due to lack of collateral. And the social welfare maximization through SHGs is the panacea to the problem of mission drift and lack of financial sustainability (Armendáriz & Morduch, 2010). Data highlight that the self-help group is the apparatus to achieve this objective of financial inclusion and sustainability through social capital. Open code of homogeneity of group members highlights that in a group, the members who know each other or are homogenous in terms of profession come together to form a group through a social contract with joint liability and limited individual liability, which helps to reduce the adverse selection. Various respondents during the interview emphasized that the members knowing that default even by one member will lead to denial of a loan to the entire group monitor each other and exert social pressure. The leader in the group enforces group norms such as regular meeting, preparation of books of accounts to facilitate regular repayment of loans. Thus, it was concluded that the apparatus of SHGs works through the peer mechanism and social control facilitated through norms, which helps in achieving social exchange and social cohesion (Stiglitz, 1990). This empowers poor and marginalized women to shatter the glass ceiling of banking, allowing them to access services without relying on social collateral and to challenge the financial biases of commercial banks that favor the wealthy and privileged (Chen et al., 2016). Therefore, considering and interpreting the data from the focused codes, the theoretical model that emerged was that the peer mechanism reduces the instances of bank loan default and improves the repayment rates, leading to social welfare (Conning, 2005; Stiglitz, 1990). Figures 1–6 demonstrate how categories of social control, social cohesion, social norms, social welfare, and sustainability assimilate the dynamics of peer mechanism in a group in the form of peer mechanism through peer selection, peer monitoring, and peer enforcement and lead to group effectiveness through transformation.

Future Research

This article will add to the existing research in the domain of peer monitoring in the context of the SHGs. And the study will corroborate the current financial intermediation and microfinance literature in the domain of group lending.

Limitations

The limitation of the study is that it does not take into account the size of the groups and the impact of digitization on the financial inclusion of the SHGs. Thus, more research can be conducted in the domain of the impact of size and digitization on the financial sustainability of the groups in India.

Conclusion

The study provides a theoretical framework for evaluating the impact of SHGs on the financial inclusion of the poor. SHGs have emerged as an important mechanism for providing microfinance to the people at the bottom of the pyramid. Within the social contract of SHGs, the peer mechanism plays an important role in ensuring access to the financial services for the micro-poor. This study provides a conceptual framework of various dynamics that help to resolve the issue of information asymmetry in a group. In a group social exchange, social control, social influence, sustainability, and social welfare play an important role in promoting the financial inclusion of all the poor people at the bottom of the pyramid. A joint liability group helps in reducing the information asymmetry in the form of adverse selection and moral hazard in a group. The homogenous set of people with common professional backgrounds and geographical proximity come together to access finance. Due to the presence of joint liability, the members’ peers monitor each other to ensure the financial and institutional sustainability of the groups and social welfare. The study provides a theoretical framework for evaluating peer mechanisms’ impact on the financial outcome of the SHG. This study will add to the current research on peer monitoring in the context of SHGs in India. This study will theoretically corroborate the current financial intermediation and microfinance literature in the domain of group lending.

Theoretical Implication and Practical Relevance

The research study has a lot of practical relevance for the policymakers, academicians, and bankers. Since independence, priority lending has been a major issue for the policymakers and the Government of India. But mission drift or the tradeoff between the financial sustainability and social objectives faced by the banks has been a major obstacle in achieving the goal of financial inclusion for the poor people at the bottom of the pyramid. This grounded theory will provide insights to the policymakers on the design of the policies for the financial inclusion of the people at the bottom of the pyramid. Moreover, the study immensely adds to the existing literature in the field of financial inclusion through microfinance.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Nishi Malhotra  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0000-3749

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0000-3749

Akerlof, A. G. (1970). The market for “lemons”: Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84(3), 488–500. https://doi.org/10.2307/1879431

Angelucci, M., Karlan, D., & Zinman, J. (2015). Microcredit impacts: Evidence from a randomized microcredit program placement experiment by Compartamos Banco. American Economic Journal, 7(1), 151–182.

Armendariz, B., & Morduch, J. (2007). The economics of microfinance (2nd ed.). MIT Press.

Banerjee, A. V., Besley, T., & Guinnane, T. W. (1994). Thy neighbour’s keeper: The design of a credit cooperative with theory and a test. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109, 491–515.

Baruah, P. B. (2012). Impact of microfinance on poverty: A study on twenty SHGs in Nalbari district, Assam. Journal of Rural Development, 31(2), 223–234.

Basu, P., & Srivastava, P. (2005). Scaling-up microfinance for India’s rural poor [World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 3646]. World Bank.

Besley, T., & Coate, S. (1995). Group lending, repayment incentives and social collateral. Journal of Development Economics, 46(1), 1–18.

Bhaduri, A. (2006). Provision of rural financial services. In Employment and development: Essays from an unorthodox perspective. Oxford University Press.

BIRD. (2019). Trend report on financial inclusion in India 2020–2021. Centre for Research on Financial Inclusion and Microfinance.

Brundtland, G. (1987). Report of the world commission on environment and development: Our common future. United Nations General Assembly document (Report No. A/42/427). World Commission on Environment and Development.

Campbell, D. T., & Fiske, D. W. (1959). Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 56(2), 81–105. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0046016

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage Publications.

Chen, X., Zhou, L., & Wan, D. (2016). Group social capital and lending outcomes in the financial credit market: An empirical study of online peer-to-peer lending. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 15, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap. 2015.11.003

Conning, J. (2005). Monitoring by peers or by delegates? Joint liability loans and moral hazard [Economics Working Paper Archive at Hunter College 407]. Hunter College Department of Economics. https://econ.hunter.cuny.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/RePEc/papers/HunterEconWP407.pdf

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Grounded theory designs. In J. W. Creswell (Ed.), Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (Chapter 13, pp. 422–500). Pearson.

Crotty, M. (1998). The foundations of social research: Meaning and perspective in the research process. Sage Publications.

DAY NRLM. (2014). English demo on Aajeevika SHG Bank linkage portal FINAL with voice. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ANu5McIAYIY

DAY NRLM. (2017). A handbook on self help group bank linkage programme. Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India.

de Quidt, J., & Haushofer, J. (2016). Depression for economists [NBER Working Papers No. 22973]. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Deininger, K., & Liu, Y. (2009). Longer-term economic impacts of self-help groups in India [Policy Research Working Paper Series No. 4886]. World Bank.

Demirguc-Kunt, A., Klapper, A., Singer, D., Ansar, S., & Hess, J. (2018). The global findex database 2017: Measuring financial inclusion and the fintech revolution. World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/29510

Easterby-Smith, M., Thorpe, R., & Lowe, A. (2002). Management research: An introduction. Sage Publications.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. The Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. https://doi.org/10.2307/258557

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine.

Gugerty, M. K. (2007). You can’t save alone: Commitment in rotating savings and credit associations in Kenya. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 55(2), 251–282.

Harriss, J., & Renzio, P. (1997). Policy arena: Missing link or ‘analytically missing’? The concept of social capital. An introductory bibliographic essay. Journal of International Development, 9(7), 919–937.

Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics 3(4), 305–360.

Ledgerwood, J. (1997). Microfinance handbook: An institutional and financial perspective. World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/12383

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (2000). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences. In Y. S. Lincoln & E. G. Guba (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 163–188). Sage Publications.

Pitt, M., & Khandekar, S. (1998). The impact of group-based credit programs on poor households in Bangladesh: Does the gender of participants matter? Journal of Political Economy, 106(5), 958–996. https://doi.org/10.1086/250037

Puhazhendi, V., & Badatya, K. C. (2002). SHG-bank linkage programme for rural poor—An impact assessment [Paper presentation]. SHG-Bank Linkage Programme Seminar. National Bank for Agriculture and Rural. https://www.findevg

Ray, D. (1998). Development economics. Oxford University Press.

Sanae, I. (2003). Microfinance and social capital: Does social capital help create good practice? Development in Practice, 13(4), 322–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/0961452032000112383

Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2009). Research methods for business students. Pearson.

Stiglitz, J. E. (1990). Peer monitoring and credit markets. The World Economic Bank Review, 4(3), 351–366. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3989881

Von Pischke, J. D. (1996) Measuring the trade-off between outreach and sustainability of microenterprise lenders. Journal of International Development, 8, 225–239. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1328(199603)8:2<225::AID-JID370>3.0.CO;2-6

Weber, O., & Ahmad, A. (2014). Empowerment through microfinance: The relation between loan cycle and level of empowerment. World Development, 62, 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.05.01

World Bank. (2020). Self help group linkage: A success story. World Bank